Changing the Industry

Family control of the Marks & Spencer boardroom ended in 1984 when Marcus Sieff retired as chairman. The new chairman, Derek Raynor, broke with the past and brought new ideas to Marks & Spencer.

In the 1980s there was a lull in the performance of the company due to growing competition from fashion chain stores. Consumer demand became more diverse and hard to please, demanding small runs of products that sold before fashions changed. Marks & Spencer needed to respond to this situation to maintain its position.

The way ahead

Investment in new technologies had improved the efficiency of firms and reduced production costs per unit. Marks & Spencer, aware of falling manufacturing costs, sought to negotiate a better deal with their suppliers and increase their profit margins and secure savings by placing orders with fewer suppliers. A preference was stated for dealing with a small number of factories dedicated solely to Marks & Spencer production. In 1987, after initial investigations, Marks & Spencer suggested to suppliers that they should consider opening overseas factories to achieve further cost savings. Courtaulds, with its previous international experience, was one of the few companies that took up this idea.

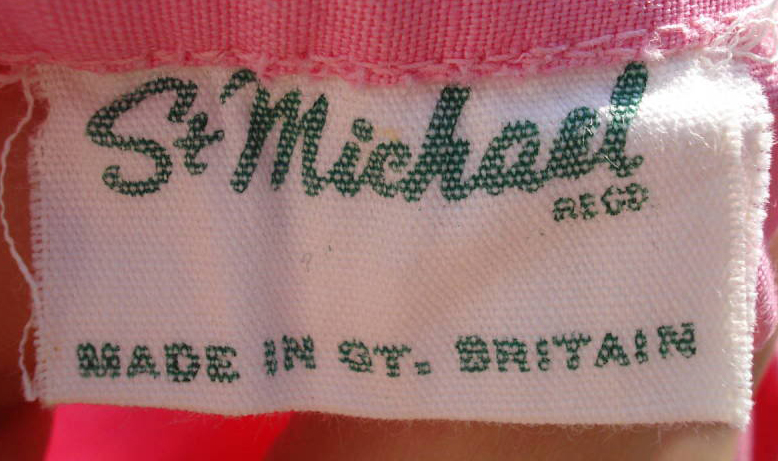

Marks & Spencer specifications and control

Suppliers to Marks & Spencer became increasingly dependent upon the design and technical services provided by Marks & Spencer. Orders were usually placed with companies on the basis of a specified number of units of a Marks & Spencer designed garment in a specified yarn, needle gauge, and dye, for delivery on a particular date. Companies that mainly supplied Marks & Spencer had no need to maintain an extensive product development section when Marks & Spencer was undertaking most of the work for them. In the 1980s this approach changed and Marks & Spencer turned to its suppliers to undertake more of the design work and come up with new ideas. The Marks & Spencer Merchandising Development Department closed in 1985. For many smaller companies, the change created resource problems. Skills and expertise that had previously been supplied by Marks & Spencer now had to be developed within the company. New relationships with innovative overseas companies were adopted by Marks & Spencer as a fallback against suppliers failing to develop new products.

The introduction of electronic technology in the 1990s increased the level of information available to Marks & Spencer buyers. EPOS (electronic point of sale) tills fed details of sales of goods back to head office where buyers could electronically order further supplies from the manufacturers. The system helped to ensure that stocks of goods were continuously replaced as they were sold.

Old and new suppliers

For over half of the twentieth century a number of knitting manufacturers had enjoyed a secure and profitable relationship with Marks & Spencer. In the 1980s, competition in the retail world began to threaten this relationship and Marks & Spencer began to look at new ways of working with their existing suppliers as well as finding new suppliers. The safety of the relationship had, however, created two weaknesses in companies; loss of brands and over-reliance on one customer for orders. Of the clothing brands sold in the UK in 1996, 85% were owned and developed by the retailers. Only 15% were brands owned by the manufacturers. In such circumstances, the loss of a contract with a retailer would leave companies without the strength of a brand behind them. Some companies tried to reintroduce brands, but it required major financing to pay for advertising and none succeeded.

Regular orders from retailers like Marks & Spencer discouraged suppliers from looking elsewhere for customers. In comparison with other European countries, British textile companies were exporting only a small proportion of their output. Before 1950, wholesalers had played an important role in securing overseas sales, but the rise of major retailers had weakened the wholesale sector to the extent that it was no longer able to undertake this role. If a contract with a retailer was lost, the company could find that it was left desperately looking for new customers to stay in business.