Workshop to Factory

The development of steam-powered knitting machines encouraged firms to invest in new machinery and buildings to house these large machines.

Companies that had previously only operated warehouses to collect goods brought in by knitters now had large premises from which workers manufactured their goods. Pagets of Loughborough established their first steam-powered factory in 1839 followed by Hine & Mundella in Nottingham in 1851. Corah established its St Margaret works, Leicester in 1865 and I. & R. Morley opened its first factory in Nottingham in 1866.

Hine & Mundella

Hine & Mundella (known as the Nottingham Manufacturing Company (NMC) from 1864) benefited from its exclusive access to the Cotton machine. The company had expanded its workforce from 52 framework knitters in 1844 to 2,000 employees by 1887. The new factory, built in 1851, was extensive in scale and had long high galleries that were compared with the interior of Crystal Palace. The company built a further factory in Loughborough in 1859 and established a European factory in Chemnitz, the centre of the German knitting industry, in 1866. Expansion was also achieved through takeovers. I.I. & I. Wilson were bought out in 1866 and their warehouse in Wood Street, London became a valuable resource for NMC.

Richard Mitchell

Richard Mitchell, a successful merchant hosier, pioneered the factory system in Leicester. In 1851 he opened a steam-powered factory with around 60 powered wide frames. He also continued to use 700-800 old-style frames for high quality work. However, his reliance on older technology led to rivals overtaking his leadership in Leicester.

Corah

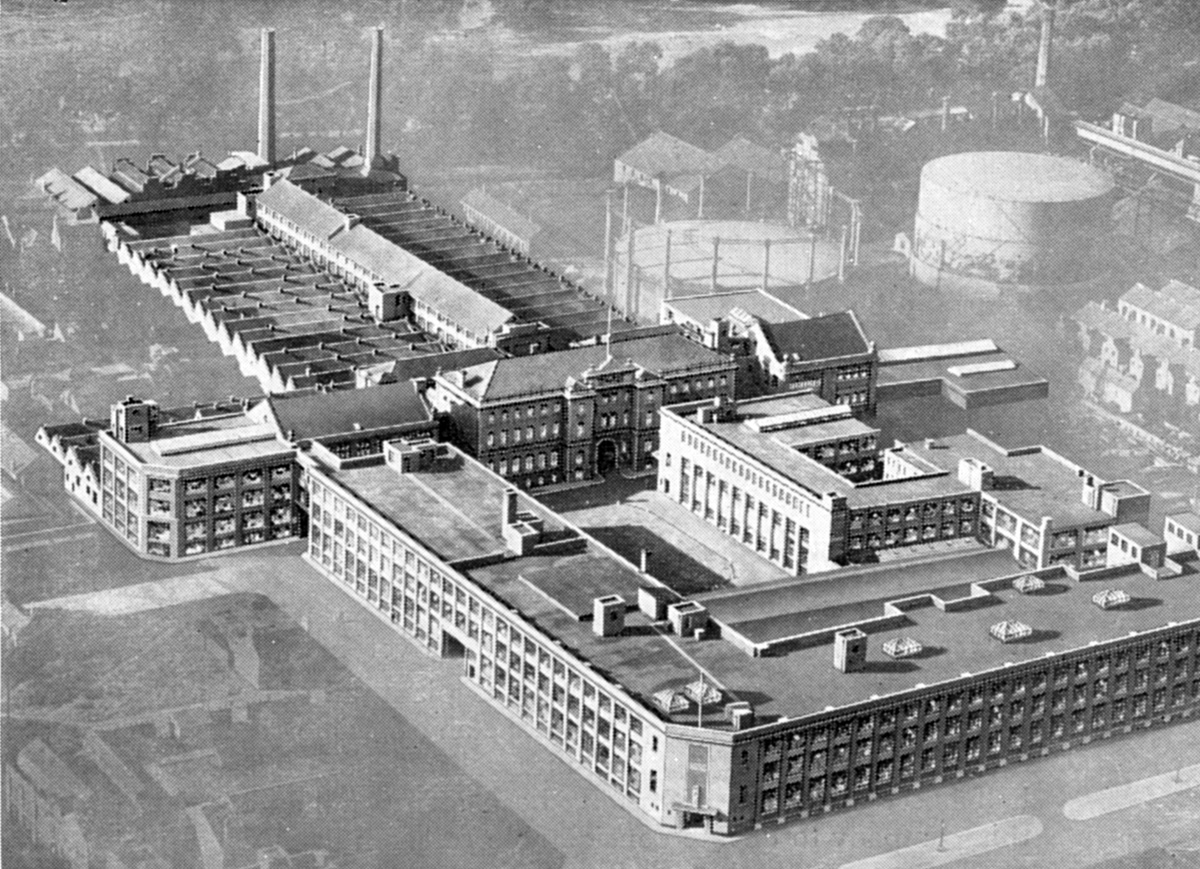

In 1865 Edwin Corah laid the foundation stone of Corah's St Margaret's Works. The factory was the largest in Leicester at the time, with around a thousand people employed at the site. The site's 50 horsepower steam engine powered 50 rotary machines, 47 circulars, and 77 sewing machines. The factory also used 28 hand frames for high quality products.

St Margaret's works allowed the company to move from domestic to factory-based production. In 1855 the company had over 2,000 domestic workers and around 20 factory employees. By 1886 all of the company's employees were factory based. Improvements in technology allowed the company to maintain its output levels and cut its workforce.

Corah's St Margaret's Works

Morley's makes its move

By the late 1860s Hine & Mundella were starting to lose ground to other competitors, particularly I. & R. Morley. Samuel Morley had taken control of Morleys in 1860 and started to make changes. A new warehouse was built on Wood Street with a design to impress visitors and look grander than other warehouses on the street. The company also constructed a series of factories across the East Midlands region including Nottingham, Leicester, Sutton-in-Ashfield and Loughborough. By the time of Samuel Morley's death in 1886 the company's payroll had peaked at 10,000 employees. The company's reputation for quality won many customers and enabled it to become suppliers to the royal family. The product range was also extensive with around 5,000 lines by 1860. Later catalogues sent to potential customers were up to 500 pages long and contained between 40,000 and 50,000 items.

Circulars in Hinckley

Hinckley's early factories were founded in the 1850s for circular-machine production. Thomas Payne opened the town's first factory in 1855 with 40 circular machines. An 1863 report recorded that five steam-powered factories had been constructed in the town during the previous decade to replace hand frame production.

Homework continues

In many cases, the opening of a factory did not end a company's relationship with framework knitters working from home. Companies had significant capital invested in frames and continued to pass work out to them and receive frame rents back. Hine & Mundella employed 300 workers in its factory in 1857 and around 3,000 domestically based framework knitters and workers. Even at the turn of the century (1900), I. & R. Morley employed more domestic workers (3,950) than factory workers (3,173) or warehousemen (1,241). Brettles employed a number of women outworkers known as 'cheveners'. The cheveners embroidered decorative designs on stockings and socks.