Transition to Factory Production

Framework knitting was traditionally carried out in workers' homes. Hosiers supplied yarn to the workers, children commonly wound the yarn onto bobbins, men knitted it into stockings and women seamed and embroidered the stockings. The industry could keep the whole family occupied.

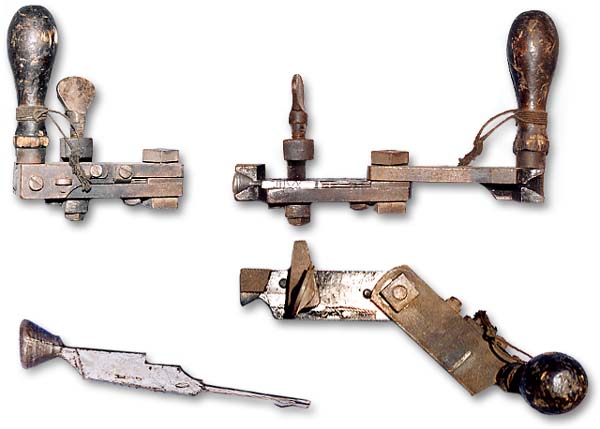

Needle moulds for handframes.

During the eighteenth century many industries, including other branches of the textile industry, transferred from domestic to factory production. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the knitting industry had still not made the transition to factories. A number of reasons were suggested for this. Framework knitters were resistant to any move that brought greater control over their work. Working at home, the knitter could determine his hours of work and share his workload with other members of the family. In contrast, the factory environment was associated with regulated hours and being watched over by supervisors.

The system of renting frames provided employers with a reason to continue domestic production. Individuals had invested heavily in frames and benefited from the good rate of return from frame rents. The cost of frame and workplace maintenance (machine oil, candles, heating, etc.) was also the responsibility of the knitter at home under the domestic system. Transition to a factory system would require the employer to cover these costs. Also, if the employer had insufficient work for his frames, the frames had to be shut down and earned no money.

While these reasons were widely suggested at the time and have some substance, they miss the crux of the problem. Hosiers and knitters alike were hostile to the new technologies of warp knitting and circular knitting, which they regarded as greatly inferior to the traditional fully-fashioned knitting on Lee's principles. The initiative was left to the French and Americans (circular knitting) and the Germans (warp knitting) so the British industry gradually lost the competitive edge.

Redesigning the workplace

Despite these resistance factors, some factory-style developments started in the eighteenth century. Property developers and hosiers realised that money could be made by building houses with rooms designed to accommodate knitting frames. The houses were often built in rows and focused knitting activities in one location. Houses in Bramcote, Nottingham were built with a communal workshop on the third floor that ran through all the properties in the row.

Separate workshops were built to accommodate a dozen or more frames, particularly the new wide frames. Too large for domestic living accommodation, these frames were often located in 'frameshops' at the rear of properties. A Wigston hosier built a two-storey workshop to the rear of his house to accommodate around twenty frames. The building survives today as the Wigston Framework Knitters Museum. Similarly, a Ruddington bag hosier called Parker built large workshops behind his cottage which survive as Ruddington Framework Knitters Museum. Frameshops were common throughout the region.

The larger frameshops can be seen as the early factories of the knitting industry. They brought the framework knitters to a single location and enabled the hosier to control his workers. Elements of the domestic industry continued to exist with the frameshops. Hand frames were still used and they continued to be rented to the workers operating them. Employers also introduced a new charge, 'standing rent', to cover the cost of the knitter using the workshop instead of his house.