Raising Standards

Since the fifteenth century patents have been granted to encourage inventors to make new discoveries. The award of a patent provides the inventor with legal protection against others copying the idea within the kingdom.

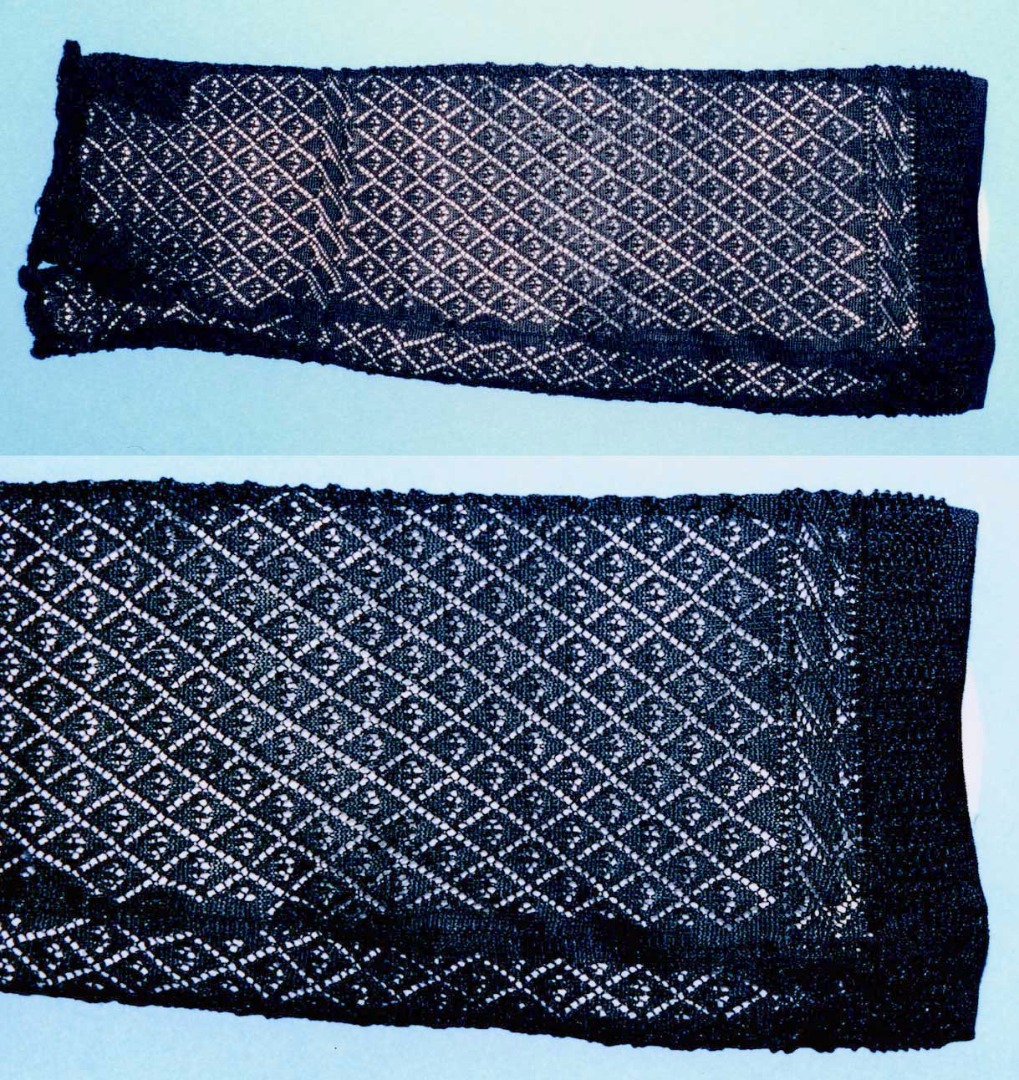

Fine lace mittens.

The Crown controlled early patents and applications were often refused if the monarch did not like the idea. William Lee had his application turned down by Elizabeth I because she thought Lee's frame produced an inferior product and could threaten jobs in the hand knitting industry.

Patent legislation

Up to the eighteenth century patents were generally applied to mechanical inventions or processes and not to artistic designs. The situation allowed knitters to freely copy the designs of other firms. The 1787 Design and Printing of Linen Act was the first attempt to apply legal protection to designs. The Act provided copyrights to people involved in the 'arts of designing and printing linens, cottons, calicos and muslin'. The copyright holder, under the terms of the Act, had the sole right to print the design for a period of two months. The two month period was extended to three months in 1794.

The Copyright of Design Act, passed in 1839, updated legislation and extended the protection provided to designers. The Act covered designs in wool, silk, hair, and mixes of fibres containing two materials from linen, cotton, wool, silk, or hair. Legal protection provided by the Act included the shape, decoration and construction of the garment. A Registrar was appointed by the Board of Trade to manage the registration system. To receive protection under the Act, the design of a garment had to be registered with the Registrar before it was made publicly available. A further act in 1843 offered extended protection for designs and revised the application procedure. The new Act made provision for applicants to provide a description of the design and note which parts were not new.

Registering designs

East Midlands companies sent representatives to the Board of Trade office in London to register their new designs. A charge was made for the registration, which ranged from a few shillings to several pounds. An example of the garment was then glued into a register for official records and a second example attached to a certificate for the company to keep. The certificate recorded the registration number, the name of the copyright holder, the date of registration, the length of the copyright period and the copyright mark to be shown on registered designs when they were sold. Details were also entered into a logbook. Usually the copyright period was for one or two years. Between 1843 and 1883 all registered designs were marked with a diamond motif that could be used to identify registration details. The marks were either stamped onto the fabric or a paper label.

The introduction of legal protection for designs led to the production of a range of unique designs by manufacturers. The registered design books held today by the Public Record Office contain many examples of knitted garments from the Victorian period.