The Emergence of Trade Unions

The Stocking Makers' Association for Mutual Protection, formed in 1776, was the first association in the knitting industry to formally represent the workers.

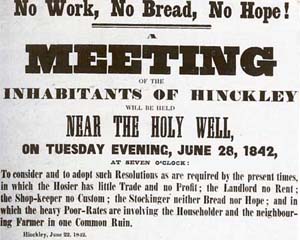

Headline about the poverty of the framework knitters in the 1840s.

The Association campaigned for a Bill to regulate framework knitters' wages, but when the Bill failed in 1779, the association fell apart. Workers continued to campaign against low wages with the support of their trade societies. If framework knitters went on strike against a hosier that had reduced pay rates, the society would use its subscription income to provide the strikers with money.

Acting against the unions

The Union Society of Framework Knitters became one of the most successful societies, with members across Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, London, Godalming, Tewkesbury and Northamptonshire. From its foundation in 1812, the Union had established a set of minimum rates, which if not met, resulted in strike action being taken against the hosier. However, such groups were illegal. The Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800 banned societies formed with a political purpose or that interfered with trade. Despite its success, the Union collapsed after three of its committee members were prosecuted under the Acts and sentenced to a month's hard labour.

The threat of prosecution delayed the formation of further organisations. Periodically, hosiers would meet with knitters and receive their complaints about wage levels. Where agreements were reached at these meetings a new list of rates was drawn up, but without a body to police them, the agreed rates were soon ignored as people agreed less pay in order to gain work.

Lobbying Parliament

Informal groups of framework knitters campaigned for a new Bill in 1819. The Bill proposed to ban production of cut-ups and bring a stop to downward pressures on wages. After discussion in Parliament, the Bill was thrown out. Framework knitters reacted by agreeing to a widespread strike across Derbyshire, Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire with the aim of increasing wages. A total of 14,000 workers joined the strike and there was wide support from the general public, who contributed in the region of £800 to finance the striking workers. The strike in Nottingham forced sixty-seven out of ninety hosiers to sign an agreement that raised stocking rates from eight to twelve shillings a dozen. The strikers, with their funds spent, were forced to return to work before all the hosiers had signed up to the new rates. Within a year, gains made by the strike were lost. Leicester knitters were the only exception to this; they were able to keep the rates for two years.

Striking again

A further major strike was called in 1821. Knitters again campaigned for rates to be increased in the industry. For over eight weeks the strike was widely supported and virtually nothing was produced across the three counties. An upturn in demand for knitted goods encouraged the hosiers to raise their rates temporarily and end the strike. The achievements of the strike were soon lost as knitters undercut each other to gain work. This cycle was repeated again in 1824 when knitters were on strike for four months. The lack of money and food forced the strike to end with only a few small temporary gains. The ending of the 1824 strike finally broke the will of knitters to continue the fight and union activity declined until the transition of the industry to a factory system in the 1850s and 1860s. The Combination Acts that prevented the formation of unions were repealed in 1824, but in the depressed first half of the nineteenth century unionism was slow to take hold.