Workshop of the World

Between 1840 and 1860 Britain experienced a period of rapid growth that saw many changes in the workplace and in society.

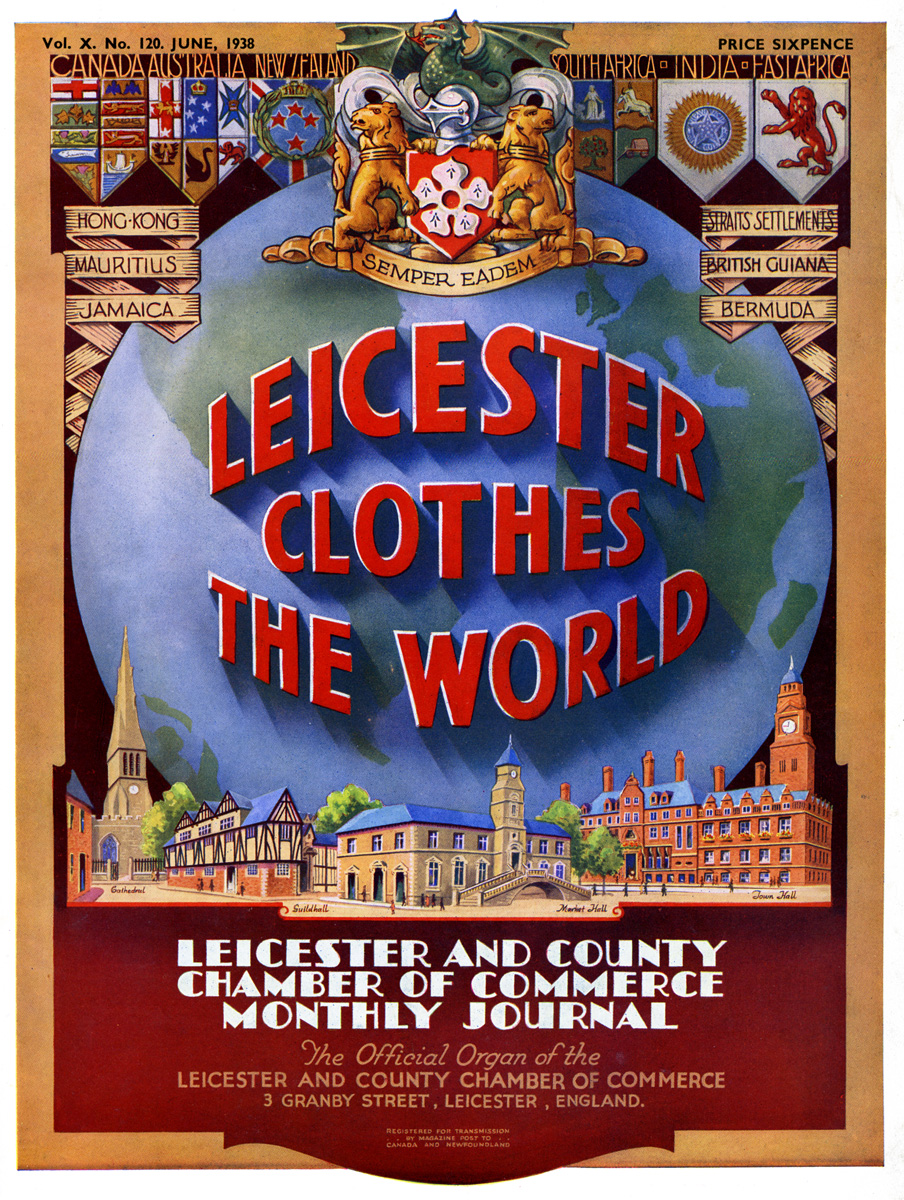

Cover of the June 1938 edition of the Leicester and County Chamber of Commerce Monthly Journal

The rail network in Britain expanded to around 10,000 miles of track, cutting travel times between many cities and towns. For the first time in history, goods could be transported across the country within a matter of hours. Opportunities for business opened up and the economy boomed. The construction of the railways alone employed 200,000 people and at its peak used 40% of the country's expanding output of iron.

The new steamships and the railways enabled Britain to trade with the world and outperform other industrialising nations, such as France and Germany. Between 33% and 50% of the world's shipping tonnage was British. The Empire and developing countries supplied raw materials and Britain used them to manufacture goods. In the knitting industry, wool came from Australia and cotton from India. Countries that supplied raw materials could use their export income to buy the manufactured goods produced by Britain and they provided important markets for British companies. Other industrialising nations also bought large amounts of British goods.

Clothing the world

Markets opened up and provided wider opportunities for sales, especially in the USA and the Empire. I & R Morley of Nottingham extended its sales force overseas to increase exports. Sales offices were opened in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, France, Germany, Belgium, Denmark, and Switzerland. Similarly, Wolsey of Leicester sold extensively overseas. In many companies export sales kept the workforce busy at times of the year when demand was lower in the British market. After sufficient goods had been made between July and December ready for the British winter, Australian orders and Canadian orders followed on from January to June. Between 1861 and 1910 exports of hosiery increased from £791,000 to £1,908,000. Much of this expansion was due to increased sales of high quality woollen goods. Sales of lower quality and cheaper cotton goods were being lost (from the 1890s) to producers in Germany. This had an impact on the industries in Nottingham and Hinckley where cotton was an important part of the production.

Export of machinery

Britain's position as the leading industrial nation enabled it to sell its technology to the other industrialising nations. Overseas industries followed closely behind the British expansion and often purchased British machinery when they did not have their own machinery manufacturers. Knitting machine manufacturers such as A Paget & Co and William Cotton & Co. Ltd supplied machines to France, Germany and USA. Overseas companies were able to examine the machines they bought and develop their own technology. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the British machinery industry experienced problems as these markets were supplied by their own domestic industry.

The competition catch up

The end of the American Civil War in 1865 created demand in the USA for knitted goods, and Britain, France and Germany competed for sales. France and Germany invested in powered machinery after realising how investments made by British companies in new technology had increased output. Mundella of Hine and Mundella, Nottingham commented to a parliamentary committee in 1868 that '...the French and Germans are catching up in the design and manufacture of knitting machines due to the excellence of their technical and scientific education. Some years ago, although the French invented the circular knitting machine such improvements were made by the English that the French re-imported them'. He also noted that '...they have succeeded by the aid of our machines and their greater intelligence in developing their manufacture more rapidly than we have'. Mundella recognised the strengths of the European industry and bought a factory in Chemnitz, Germany.