The 1844 Royal Commission

After the strikes of framework knitters in the 1810s and 1820s, wages in common branches of the industry remained at a low level for a further twenty years. Reports highlighted the poor conditions faced by workers.

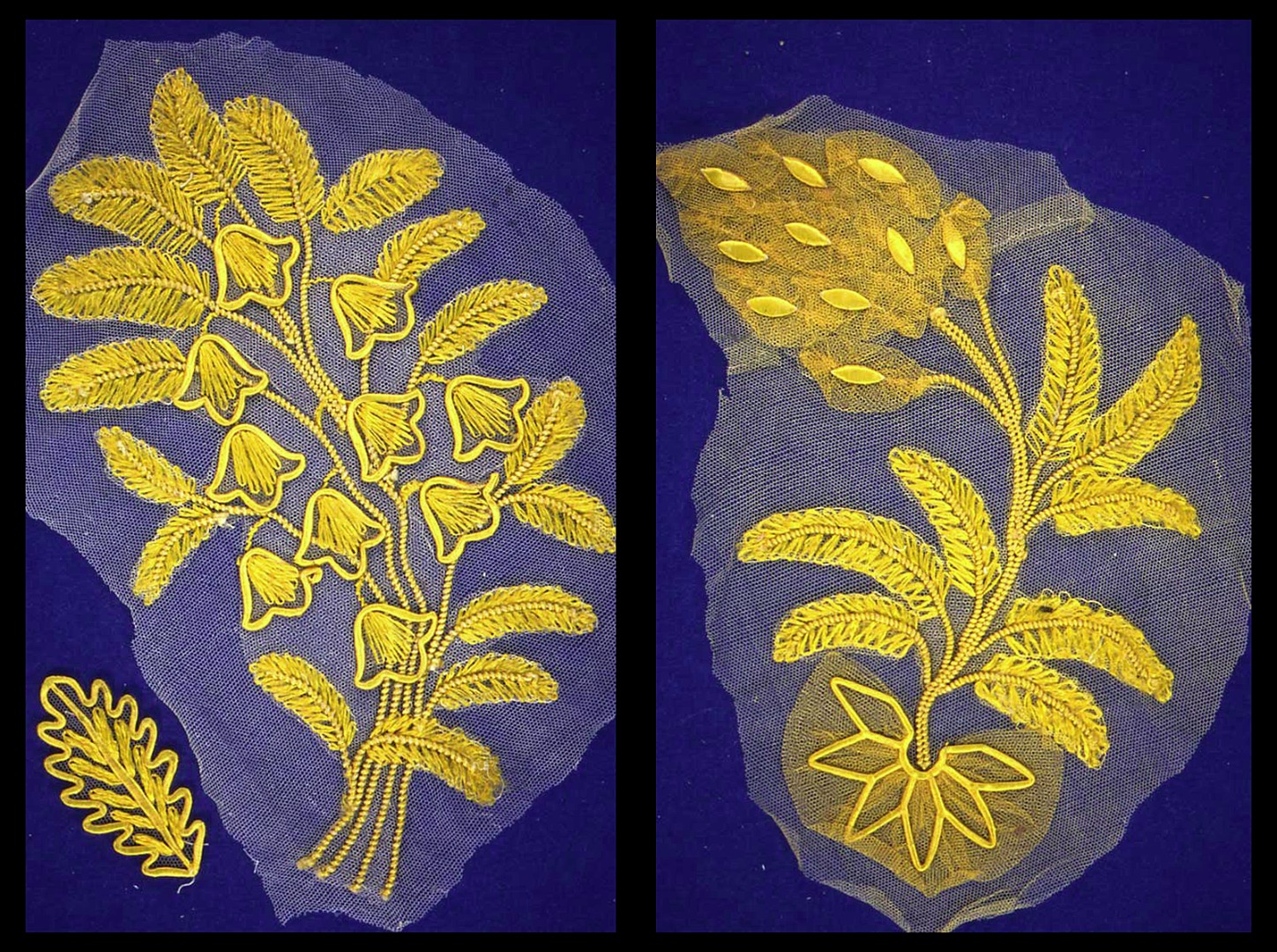

Silk Embroidery Trimming c.1827

A factory commissioner noted in 1833 that 'The men sat at their work back to back; there was just enough space for the necessary motion, but not without touching each other'. He also commented that the majority of men over twenty looked 'sickly and emaciated'.

However, demand developed in new sectors for workers who were adaptable. Innovations in products included cut-ups, gloves, drawers, shirts, caps, fancy goods, and socks. Wages of 11 shillings a week could be earned in these new lines, while basic stocking knitters were paid around 7 shillings a week. The industry continued to grow as population in Britain expanded and new markets were developed overseas. Between 1812 and 1844 the number of stocking frames in use increased from 29,595 to 48,482.

Petitions to Parliament

In 1843 framework knitters took action to campaign for improved conditions. Over 25,000 framework knitters signed a petition and submitted it to Parliament. The petition complained about wages, unemployment, new machinery, frame rents and imports of knitted goods. The Government responded by appointing Richard Muggeridge as the Commissioner responsible for compiling a report on the industry.

Commission officials spent several months in the East Midlands taking evidence from a range of people connected with the knitting industry. Framework knitters, hosiers, masters, local officials, professionals (doctors, clergymen), and the Mayor of Leicester were all received and presented their accounts of the industry.

Frame rents

The payment of frame rents was one area that particularly concerned workers. Most knitters were unable to afford to buy a knitting frame and were forced to rent their frame from the hosier. The report recorded that frame rent and other expenses (candles, oil, etc.) could amount to a third of the knitter's wage. The impact of frame rents was made worse where hosiers rented out more frames than they needed to complete the work available. The practice became known as 'stinting'. Knitters had to pay a full week's rent even when the work supplied by the hosier only took a few days. The report recorded that between 1814 and 1844 wages fell by up to 40%, while frame rents continued to rise. A John Woodward complained to the Commission that he had paid £180 in rent over twenty-two years on a frame worth £9.

Bag Men

Middlemen or 'bag men' collected work from the knitters' houses and took it to the hosier's warehouse. A 'taking in' fee was charged for the service by the middleman and deducted from the knitter's wages. Framework knitters complained to the Commission that middlemen or 'bag men' commonly underpaid them for their work, not passing on the full rate paid by the hosier. Knitters frequently demanded that lists of prices should be printed and distributed so that they knew how much they should be paid.

Knitters also complained that they were forced to buy goods from specified shops or risk not being given any further work by the employer. The employer or members of his family often owned the shops and used their position to charge higher prices or just gain an unfair advantage over other local shops.

The outcome of the Commission Report

The Commissioner's report concluded that low wages were associated with the high number of people wanting to work in the industry. Oversupply of labour had forced wage rates down. Employers who rented out more frames than required allowed people to enter the industry easily and this did not help the situation. Some witnesses acknowledged that the merchant hosiers had been sluggish in responding to the new technical and market opportunities while others complained of competition from cheap labour in Saxony. The report also recognised that higher wages could be gained by turning to new designs in better quality lines. The impact of the Commission was limited. The output of the domestic industry at the centre of the report was gradually transferred to factory production in the years following 1845.