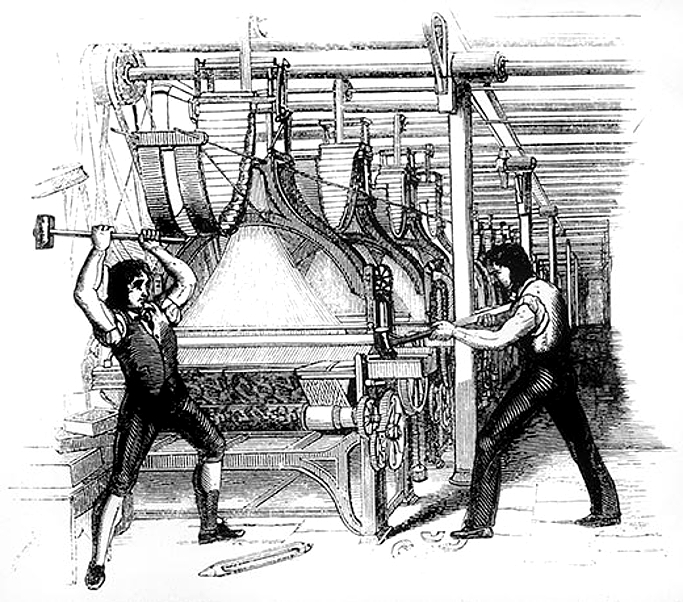

Luddite Frame Breaking

Early framework knitters were a prosperous group. An average Nottingham framework knitter in 1714 earned 10 shillings and 6 pence for a four day week; those that produced fine embroidered work could earn as much as 20 shillings a week.

Later interpretation of machine breaking (engraving from the Penny magazine)

Others soon entered the industry hoping to enjoy the same standard of living, but rising numbers diluted standards and earnings in the less skilled branches. Like all fashion-based industries, knitting was vulnerable to sudden shifts in demand and earnings were affected.

Protests begin

Unemployment in the industry sometimes resulted in framework knitters taking direct action to. In 1778 knitters petitioned Parliament for a Bill to regulate their wages and prevent hosiers or their agents underpaying them. Framework knitters also formed friendly societies to provide support in hard times. Workers paid subscriptions to societies on the understanding that they would receive money from the society if they were sick or laid off.

Knitters reacted further at the introduction of wide frames in 1776. Wide frames used more needles in a row than earlier frames and produced a wider piece of fabric. The shape of the garment was cut out of the fabric and sewn together. This type of garment was commonly referred to as a 'cut-up'. The shorter production time and less skill required meant that 'cut-ups' were cheaper to produce. As a result, knitters were paid less to produce them.

Workers riot and smash

The first two decades of the nineteenth century saw a downturn in the knitting industry as fashion changes reduced demand for hosiery. Workers felt their standard of living threatened. Wages were often less than they were a hundred years earlier. Work also became scarce as the demand for men's hosiery collapsed during the turbulent Napoleonic War period. The tensions finally erupted with the outbreak of a series of Luddite riots.

In March 1811 workers tried to negotiate higher wages and force hosiers to abandon the use of cut-ups. As talks failed, groups from across Nottinghamshire gathered in Nottingham's marketplace. Troops were brought in to control the situation in the town, but they were unable to prevent widespread destruction across the county. Sixty-three frames were smashed at Arnold (north-east of Nottingham) and a further two hundred frames were destroyed across the county over the following three weeks. The riots continued into 1812, by which time the Luddites had broken up over eight hundred frames.

Rebellion spreads

During 1812, the rebellion against new technology spread to Leicestershire and Derbyshire. The plight of the workers was made worse by a rapid rise in the price of wheat. In response to the extension of Luddite actions, attempts were made to deter further disruption, 12,000 troops were ordered to take control of Luddite areas and four Nottingham rioters were sentenced to transportation. An Act was also passed making the destruction of frames punishable by death.

Controlling the Luddites

By the summer of 1812, Luddite frame-breaking had ceased in Nottinghamshire. Elsewhere, occasional outbreaks of destruction continued until 1817. Heathcoat's lace factory in Loughborough was attacked on 28 June 1816 and £6,000 worth of damage was done. Transportations to Australia and a series of hangings forced the workers behind the Luddite movement to reconsider their plans. The Luddites smashed an estimated thousand stocking frames between 1811 and 1817.