Building the Knitting Machines

Since the time of William Lee, the knitting industry has been supported by the knitting machine building industry. Before the nineteenth century, knitting frames closely followed the design of Lee's frame.

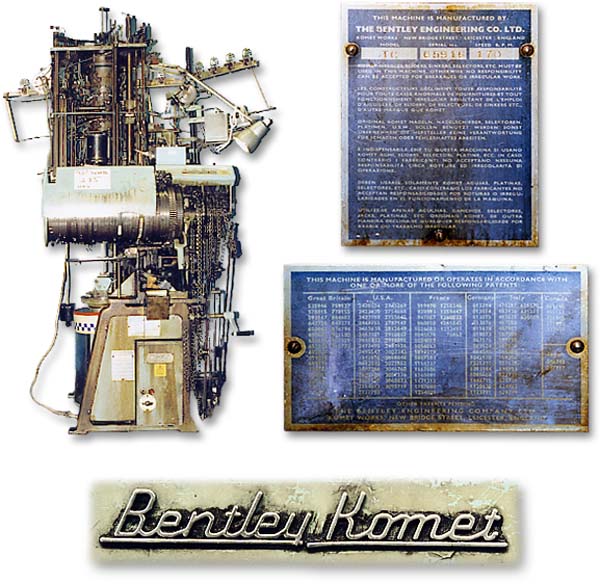

A more recent Bentley Komet Model TC machine, made in Leicester

The mid-nineteenth century saw the development of circular knitting machines and automatic fully-fashioned machinery. Leading companies of the industry for the next century were founded around this time. Moses Mellor and G. Blackburn & Co. (initially known as Attenborough & Mellor & Co.) were founded in the 1840s and 1850s in Nottingham. The next wave of innovations occurred in Loughborough during the 1860s, where A. Paget & Co. Ltd, and William Cotton & Co. Ltd. developed fully-fashioned machines.

The British knitting industry traditionally favoured fully-fashioned garments and saw circular knitting machines and wide flat frames as producing an inferior product. The Paget and Cotton machines quickly became popular in British factories and many were exported. They offered reliable service and with maintenance, some of the early Cotton machines were still in use a century later. When the Cotton patent ran out in 1879, other companies copied the design and produced their own version. The machines were commonly referred to as 'Cotton's patents'.

Knitting in circles

Overseas competition and the demand for cheap goods in the British market forced firms to use circular knitting machines. To avoid wage cuts, companies had to use a technology that would increase output, cut costs, and produce a saleable garment. The introduction of new automated processes to circular machines in the last quarter of the nineteenth century further encouraged manufacturers to invest in them. In the USA and Europe, technicians worked to develop machines capable of automatically producing heels and toes on stockings and socks. Large diameter circular frames continued to be used to produce fabric for cut-and-sew knitwear and underwear.

Selling for the competition

During the early twentieth century, the British knitting machine industry was heavily influenced by developments in the USA. Blackburns became agents for the American company Scott & Williams in 1890. The company was subsequently appointed the sole licensee, outside of the USA, for the Scott & Williams Interlock machine. The fully-fashioned industry that the UK had pioneered and led became dominated by German designs. The German company, Schubert & Salzer, was the largest knitting machine manufacturer in the world by 1928. The Textile Machine Works of Reading in the US also developed their version of a fully-fashioned machine, popularly known as a 'Reading'. Between 1945 and 1949 over 2,000 Readings were imported into the UK.

British innovation

The outlook was not entirely bleak for machine builders as companies were still able to introduce their own new machines and capture a sector of the market. Spiers and Grieves launched their 'XL' machine in 1902. The 'XL', through its various models, was the main double cylinder knitting machine until the 1970s. The success of the 'XL' was closely followed by the Bentley 'Komet', a double cylinder circular machine.

The British industry was given some help in 1932 when high tariffs were introduced on imported knitting machinery. However, companies such as G. Stibbe & Co. Ltd, and Wildt & Co. Ltd, both of Leicester, who had imported and sold machinery, found that it was no longer profitable to do so. Fortunately these companies had gained an understanding of the technology by making adaptations for clients to imported machines. Stibbe manufactured such machines as the 'Maxim', 'Challenger', 'Model T', and the PB/DR 8 feed interlock machine. Wildt introduced its 'Model E' and 'Auto-Express RJ'.

Wartime timeout

At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the knitting machine building industry employed a total of 2,766 workers. For the duration of the war, the production of knitting machinery stopped and factories were turned over to other uses. Industries vital to the war effort were moved from the areas under threat of air raids, such as the West Midlands, to the East Midlands. When peace returned, demand increased for knitting machines to replace those worn out during the war and British companies enjoyed full order books.